Up

Up

|

|

|

|

Torsion wire delay line memory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today you could fit terabytes of memory in this small metal box, but actually it contains just a tiny fraction of that: less than 200 bytes of Read/Write memory. |

|

|

|

Click a photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

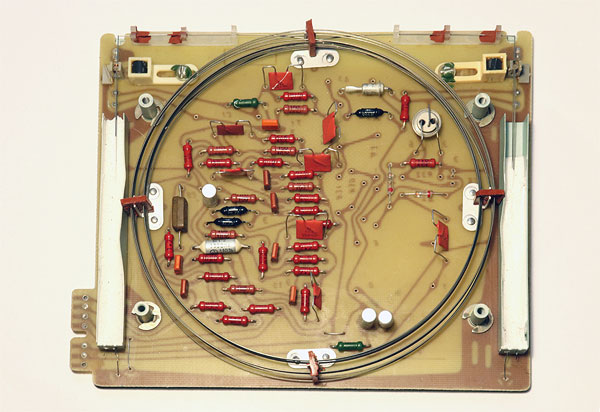

Take the cover off, and you discover an intriguing circuit board dominated by a coil of metal wire. The coil’s radius is 13 cm, and the 10 turns of wire come to about four meters in total length. |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

This is a torsion wire delay line memory

module, and the metal wire is its storage medium. The way it works

is this: for each “1” bit to be stored, a transducer twists the

input end of the wire briefly. This causes an acoustic torsion pulse

to propagate down the wire. A second transducer detects this pulse

when it reaches the other end, and feeds it back to the input

transducer; thus, the bit goes round and round indefinitely,

signifying the “1”. With proper timing, you can inject in and read

out many bits -- hundreds or even thousands, depending on the length

of the coiled wire. The only drawback is that readout is sequential

-- this is not a random access memory like your ordinary DRAM chip

or hard disk; you have to wait for the bit you want to read to

arrive at the end of the wire, which might typically take a wait of

500 microseconds. The board contains a transistor and a handful of diodes, resistors and capacitors that I suppose take care of shaping and amplifying the pulses. They are certainly not enough to implement the digital input/output logic, so that must have sat outside the module. But the interesting part is how the electronic pulses are converted into mechanical torsion in the wire. The mechanism can be seen in the photo below. |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

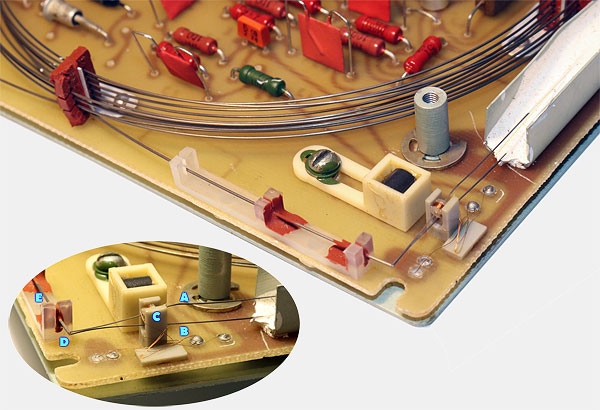

The end of the wire is seen leaving the coil

and terminating at the corner of the board. Referring to the inset,

we have two nickel wires, A and B, whose right hand side is anchored

and embedded in the white damper block while the other end connects

to the main wire E. The wires are fed through the transducer C, each

passing at the center of one of a pair of tiny, vertically stacked

electromagnets. From there they continue to the end D of the main

wire E, and are welded to opposite sides of this wire’s

cross-section. Now, nickel is magnetostrictive -- it changes its

dimensions when subjected to a magnetic field. The electromagnets

are polarized so as to expand one wire and contract the other when a

current is sent through them; supposing A is shortened and B is made

longer, the end of the wire at D will be twisted clockwise, sending

the torsional wave into E. The opposite is also true -- a twist of

the wire at the other end, which is equipped with an identical

transducer, will create a current in the coils of the electromagnets

at that end. The travel through the coil does degrade the pulse

somewhat, but the electronics take care to reshape it before feeding

it back in. Magnetostrictive delay line memory was invented in the 1950s and put to use in the 1960s in a variety of computers and desk calculators (perhaps the most famous of these was the Olivetti Programma 101 electronic calculator, introduced in 1965 and considered by many to be the first personal computer). In the 1970s this technology became obsolete in the west, but was still in use in the USSR, where the unit in my collection was made. The guy who sold it to me, who clearly knew his way around soviet electronics, said it had come from an ISKRA 111 calculator from 1976, and you can see two kinds of similar units (one with twice the wire length used in mine) in other calculators from that manufacturer, here and here. From data I have on other units I can estimate that the one I have could store anywhere between 500 and 1400 bits, depending on the clock speed used. Incidentally, this was not the only kind of delay line memory, nor the first; mercury delay lines, where acoustic waves travelled down tubes filled with mercury, came earlier, and were used in some of the early mainframes from the EDVAC on. But that is another story... |

|

|

|

Exhibit provenance: eBay, from a seller in Russia. More info: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home | HOC | Fractals | Miscellany | About | Contact Copyright © 2021 N. Zeldes. All rights reserved. |

|