Up

Up

|

|

|

|

Slide rules for a new century |

|

|

|

|

|

|

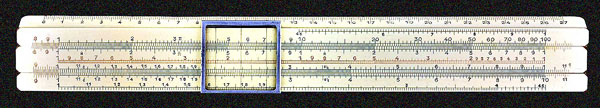

Here is a nice French Mannheim slide rule from the end of the 19th century, nicely presented in a fitted wooden box. It has two scales running 1-100 at the top and two running 1-10 at the bottom, and a cursor that allows moving between them precisely, which enables extraction of squares and square roots. |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

When the French artillery officer Amédée

Mannheim invented this new kind of slide rule in 1851, he asked the

Gravet-Lenoir workshop in Paris to productize the invention. This

was a natural choice:

Gravet-Lenoir

(who would rebrand in 1867 as Tavernier-Gravet) was a leading

scientific instrument maker, and well positioned to do justice to

Mannheim’s idea. Which was an excellent idea: since their invention

two centuries before, slide rules had been made in a plethora of

different designs, which Mannheim improved by defining the standard

set of scales mentioned above and adding the cursor, a standard

feature in all later slide rules. This arrangement remained in use

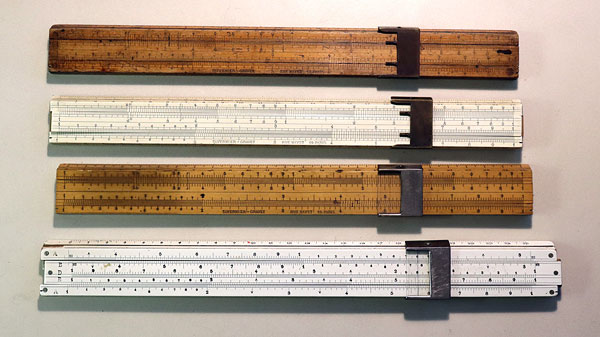

for 100 years, and was the basis for many further improvements. Over the years I’ve accumulated four Tavernier-Gravet slide rules. Three are straight Mannheims, and the fourth is a “règle Beghin”, a variant with two scales “folded” to place the 1 at the center rather than at the left edge. Each is a nice collectible, but when I recently examined them together I realized that they show an interesting trend in time (and I just love technology trends!): they represent the transition from 19th century to 20th century slide rule technology. Here they are: |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

And here is the back side: |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

We have here:

(The date ranges are deduced from the various dates present on

the backs of the slide rules and other details.)

The transition from bare wood (boxwood, usually) to a celluloid

veneer (first patented by Dennert & Pape, Germany, in 1886) greatly

improved readability of the scales; it is not surprising that it was

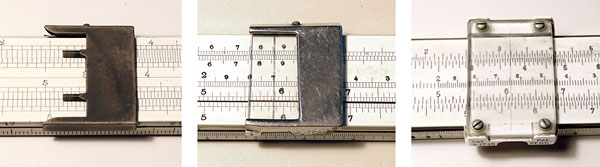

soon adopted by all slide rule makers. The change in cursor, from

brass to glass, makes a lot of sense too, since it allows unhindered

viewing of the scales. However, the examples shown here are only

halfway there: the area around the hairline is glass, but the glass

is held in a wide metal holder -- clearly adapted from the older

chisel cursor. The transition would be completed a few years later,

by T-G and everybody else, with the introduction of all-glass

structures like the one seen at the right in the image below. |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

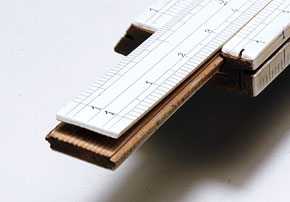

Tavernier-Gravet began the transitions to

celluloid and to glass during the 1890s, and for a number of years

were offering both materials and both types of cursors at different

price points, until the newer versions became standard. However,

slide rule #2 tells of the difficulties they’ve encountered, as

often happens with a new technology. On this rule the celluloid

layer on the slide has shrunk lengthwise -- by a noticeable 1 mm --

and in so doing it popped right off, detaching itself completely

from the underlying wood and curling up at the ends (photo at left,

below). This tells us that the company hadn’t yet mastered the art

of gluing wood and celluloid, diverse materials with different

expansion coefficients in the face of changes in ambient temperature

(and perhaps moisture). Evidently they hadn’t yet hit on the correct

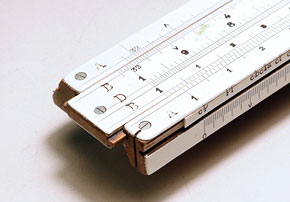

formulations of glue and other process parameters. But they did more R&D, and they improved. Slide rule #4 (photo at right)shows us their solution: it has little screws at the ends of the celluloid strips to prevent the fate of rule #2. |

|

|

|

Click a photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

These screws were first patented by Nestler

in 1901 and are seen in early celluloid-faced slide rules from a

number of manufacturers, although they later disappeared once better

materials and techniques had made them unnecessary. And here is a photo of a Tavernier-Gravet rule made in 1942, after they’d solved the peeling problem, dropped the screws, and adopted an all-glass cursor. This one is not mine, and I thank Gonzalo Martin for permitting me to show it here. |

|

|

|

Click photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

Note the little diagonal notches at the

corners of the celluloid strips… another innovation adopted by many

manufacturers to reduce the likelihood of chipping or separation of

the celluloid. Technology marches on, improving incrementally but surely! |

|

|

|

Exhibit provenance: Slide rule #1 was an eBay purchase; the other three were acquired from various fellow collectors. More info: Tavernier-Gravet catalogs and ads on the same site.

Acknowledgments: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home | HOC | Fractals | Miscellany | About | Contact Copyright © 2020 N. Zeldes. All rights reserved. |

|